Digital News Report 2025: exponential media change is here

The era of incremental media change is over, and the emerging media tsunami is upon us. It's exponential all the way from here on out.

Today is that day. If you’re interested in journalism, the Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2025 is out. The metamedia websites, newsletters and podcasts will be abuzz with stories or commentary about it. And I’m certainly no exception.

Do I have thoughts? Oh, do I. I’ve had access to an early copy for the best part of a week, and so this is less a hot take, than a well-baked and tastefully seasoned one. Rather than digging too much into the individual detail of the report (which I might come back to, time permitting) I’d like to take a more high-level approach. What does the data in the report tell us about how journalism need to change if it wants to survive? I don't want to give you the details of the report – I want to explore what you can do with the information within. There's a very good reason for that which will become apparent…

And, make no mistake, what this report makes very clear is that the digital disruption of media is not over. In fact, it’s just getting going. We’ve entered the exponential age of media change. Buckle up.

The two big themes

Perhaps the most surprising thing about this year’s report is how little is actually surprising. It paints an accurate, data-driven picture of the way the world of news is now, one that was clear to anyone paying attention. But having that in front of us in stark clarity is incredibly valuable.

I want to focus on the two most important themes I see in the report:

- News media has reached an inflection point, and has now entered exponential change

- We’re still focusing on the wrong threats and opportunities

That idea – that we’re in an era of exponential media change, has been floating in my head since the US election last year. What Nic and team have done with this report is provided that evidence that backs it up.

The exponential era of media change

The media world is unrecognisable from the way it was when I started doing digital development professionally two decades ago. But, if you just look around at what other publishers are doing, you won’t see that. You need to zoom out, and see where the competition for news attention is.

Let’s have a look at this graph:

The only traditional media form that makes it into double figures as a main source of news is TV. And it’s clear that that market is aging out badly. I have serious problems imagining my daughters ever seeing “TV“ as a main source of news in any traditional sense, when they enter the survey cohort in half a decade’s time.

The three major media types that are genuinely mainstream are:

- Social media

- News websites/app

- TV

Now, unless something fundamental changes in the next few years, the third category is going to increasingly blend into the other two. I quite genuinely can’t remember the last time I watched BBC news on the TV, rather than via the app or the web.

We’re looking at a world where the majority of people get their news first via social platforms, but the most engaged audiences will still find their way to “owned” media forms like websites and apps.

That’s our future.

If we don't get this right, we cease being the mainstream media. Indeed, there's evidence in the report that, for some strata of society in some countries, we have already been displaced as the mainstream.

Print isn’t dead, but it’s becoming a niche, valuable badge of commitment to a particular brand or cultural identity. It is no longer, in any meaningful sense, mainstream media. Broadcast isn’t dead, but the boundaries between “broadcast” TV and radio and their digital expressions will become increasingly meaningless. If you’re still doing the TV news package first, and then thinking about doing “a social”, you’re not just putting the cart before the horse, you’re feeding the cart the horse’s hay, too…

The balance of media

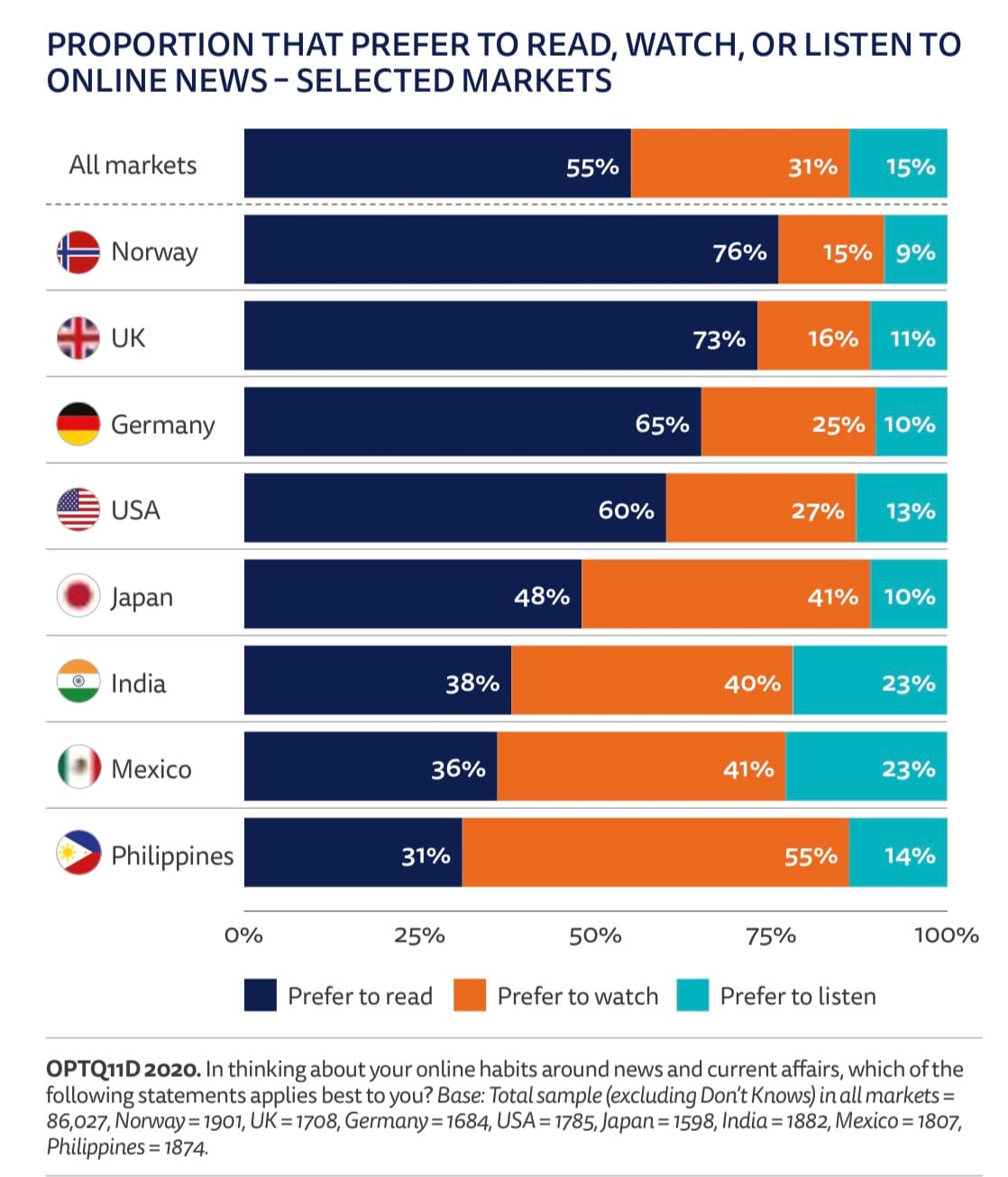

Print might be a niche product now, having followed the path of theatre after the arrival of film and then TV, but text itself is far from dead. If you like writing, there’s good news for you:

Globally, more people prefer to read news than in other formats, although there’s significant global variance in those figures.

But, if we were to do a headcount audit of most UK newsrooms, would we see 73% of staff on written news, 16% on video and 11% on podcasts? If you were to run a content audit of those organisations, how closely would it match that ratio?

I can’t prove it – and would love to be proved wrong – but my gut instinct is that every single UK newsroom that derived from print media is heavily over weighted on text. Still. 30 years after the dawn of digital, 20 years after the rise of YouTube, we’re still trapped in our text ghetto, while our brand and relationship development is going to happen everywhere else. The audience actually coming to the text and reading it is the reward we'll earn – but also part of the relationship deepening process.

Text is here to stay — even if our story formats and approaches need to change (see below). But we need to be more aggressively rebalancing our newsroom skill bases.

Video killed the textual star

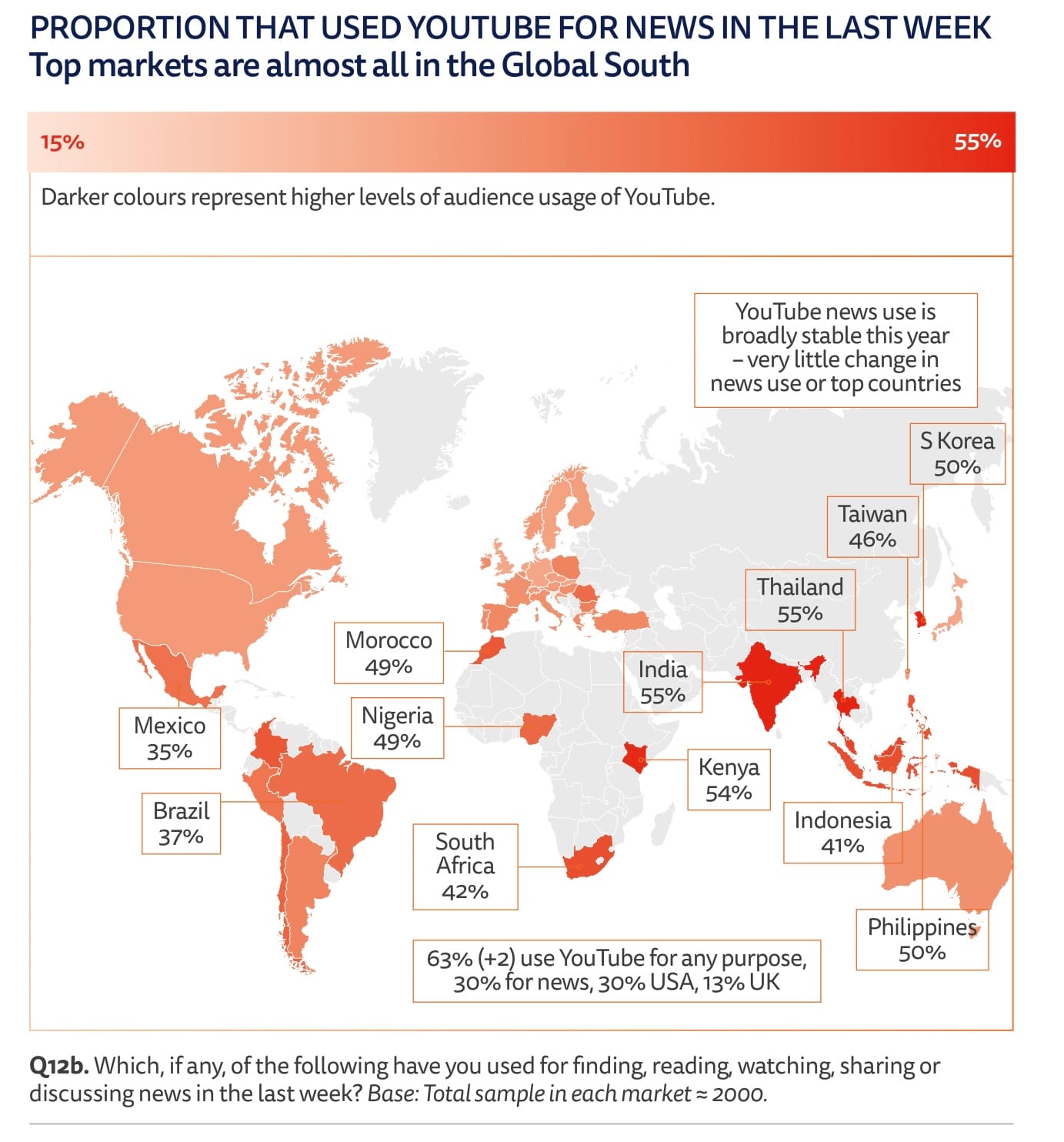

And how do things look in the video world? Well, here’s an indictment of our neophilia:

Yup, YouTube is still much bigger than TikTok. But how much have you read about publisher’s YouTube strategies of late? And how much about their vertical video strategies?

Both matter. However, YouTube, and online video formats generally, are absolutely mainstream. And they are dominated by emergent, influencer-led content, not anything that looks like traditional media companies.

We have, and have had for over a decade, a window of opportunity to take our traditional brand reputation, and transfer it into this massive pool of attention. That window is now closing. You are running out of time. Yes, vertical video is part of that equation. But it’s not the whole of it.

Rebuilding our relationship with audiences

OK, let’s follow that up with something more positive. One piece of good data is that news avoidance has stabilised over the past three years. That’s fantastic news because it gives us a platform to build off. Now that has arrested, how do we bring people back into a better relationship with us?

The report (obviously) doesn’t have an answer, as it focuses on the present. I don’t have an answer, either – but I know how we get there. We need more experimentation with both styles of journalism and formats. Take a wee peek at this:

In fact, don’t just look. Print it out. Put it prominently on a wall somewhere. And point anyone who mouths the cliché “if it bleeds, it leads“ at it. Look at how closely some of these statement match up to that style of reporting. Yes, there’s lots of bad news in the world. But both the style of our reporting on it, and the balance of it versus other news is putting people off.

Sure, tragedy, and war, and conflict generate the eyeballs. But it does so at the expense of loyalty and relationships. We shouldn’t avoid hard and difficult news because it’s critical to the job of journalism. But we need to go further with what we do with it than we do now. We need to be better at contextualisation and reporting of solutions, if we want people to read what we do.

News is not an abstract art. It is a service performed for the benefit of a population. If they don’t find it beneficial, we are at fault, not them. This, coupled with us failing to adapt to format shifts, is the most difficult challenge lurking at the heart of the report. And it’s been there for some years. But, it seems, we would rather not focus on it because it involves reworking the way we think about the journalistic process.

Back in my B2B days, we had a big focus on “news I can use“. Drawing a clearer connection with what I’m reading, and what could address these problems, is more likely to make me feel better about the journalism, and make me more likely to keep coming back to your reporting.

A note of caution

Remember, the report focuses on two things:

- News, rather than journalism. (News is a subset of journalism.)

- Mainstream, rather than niche. (The more niche your audience, the more their behaviours will vary from these baselines.)

I would hesitate, for example, to apply these findings directly to a B2B publishers, whose trade audiences might vary wildly from these base figures. (It’s been years since I worked with Farmers Weekly, but I’d be really interested in the balance of video versus text that works for that audience, given that my experience, back in the day, was that farmers were a surprisingly visually orientated audience.)

That said, it makes a really useful starting point. The trick involves working out how, why and to what degree your audience deviates from the baseline.

And what about the wrong threats?

Right now, everyone is talking about AI. It is a threat, and a future issue, but we’re rushing ahead in trying to solve tomorrow’s problem without addressing today’s problems. That’s an all-too-common mistake.

AI mediation of news is almost certainly coming. But it’s only in the single figures as a percentage for most generations, and even among the young, the figure is around 15%. There’s strong audience wariness of AI-generated news, and growing real-world experiences of AI just being plain wrong in many situations.

So, yes, of course we need to pay attention to it. But if our AI efforts are an order of magnitude larger than our exploration of how to make video work better for our newsrooms, or how to translate engagement on vertical video platforms into more profound relationships with our brands, or finding better formats for more solutions-oriented reporting, then maybe our priorities are askew.

One of my great unwritten articles, that exists as one of a series of part-finished drafts, is about the fact that there is no profound threat to journalism. Journalism will survive. What is under threat are the current jobs, companies and formats we use to disseminate journalism. The only way to preserve the first two, is to focus on the last one.

Fundamentally, many news outlets still produce the majority of their output in formats that were designed for either the printed newspaper or the TV broadcast slot, or as optional social “add-ons” to those.

The report makes it very clear that reading newspapers for news is now an incredibly niche activity. That doesn’t mean that it’s time for us to abandon the 350 word inverted pyramid story, but it does mean that we shouldn’t consider that as both the main and the default format we communicate news.

Building a new toolbox

Tomorrow, I’m off to do an in-house training course for a publisher, and I’ll be talking to their staff about the audience strategy toolbox; the range of engagement tools we can deploy to deepen our relationship with our audiences. It’s time for any news-focused organisations to think about a content strategy tool box; about the range of tools we have to communicate a news story.

And it might well be that those formats don’t yet exist. That’s literally what news influencers are doing on social platforms: running experiments, figuring out how to make it work, figuring out how to monetise it. That’s what we should be doing. Now, to be sure, some places are doing that. But not enough.

And those are the businesses – and the jobs – that are under threat. Ask yourself this: as you look around the news organisation you work for (if you do). Are you confident that it understands this fundamental shift in how people consume news (and, by extension, all journalism)? If not, and you have no ability to shift that, you need to acknowledge that your time there will be limited, one way or another.

We’re in the exponential change era for media. We don’t survive exponential change by incremental improvements in what we do. The digital transformation of media is accelerating. We have to keep up, or be supplanted by a whole new breed of journalism…